The prevalence of bipartisanship in U.S. foreign policy: an analysis of important congressional votes

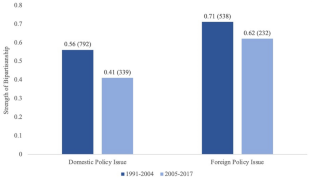

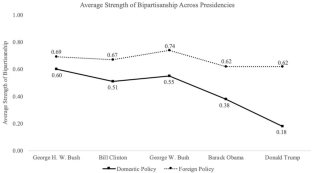

To what extent are U.S. elected officials polarized on foreign policy? And how do patterns of polarization and bipartisanship differ across policy areas? Using an original data set of nearly 3000 important congressional votes since the end of the Cold War, we find that severe polarization remains the exception rather than the norm in U.S. foreign policy debates and that the U.S. Congress is still less polarized on international than on domestic issues. We also show that foreign policy bipartisanship regularly takes several forms, including bipartisan agreement in support of the president’s policies, cross-partisan coalitions, and even bipartisan opposition to the president’s policies. Collectively, our findings provide a more nuanced portrait of the politics of U.S. foreign policy than many recent accounts, point to persistent differences in the political alignments associated with different policy areas, and highlight the importance of conceiving of polarization and bipartisanship as more than binary categories.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Springer+ Basic

€32.70 /Month

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Buy Now

Price includes VAT (France)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Similar content being viewed by others

Partisan polarization and US foreign policy: Is the centre dead or holding?

Article 01 September 2016

Beyond party: ideological convictions and foreign policy conflicts in the US congress

Article 21 January 2022

The impact of party conflict on executive ascendancy and congressional abdication in US foreign policy

Article 13 July 2021

Notes

Cross-partisanship is not mutually exclusive with pro-presidential or anti-presidential bipartisanship.

CQ Almanac articles highlight important congressional votes in a given year in two ways—first, in a list of about 20–30 “key votes,” which represent the most important votes of the year; and second, in articles summarizing congressional activity in various issue areas during that year, which typically list the most important votes in each issue area in a text box labeled “Box Score.” The data set includes any votes listed as “key votes” or directly referenced in one of these box scores. For articles lacking a box score, the data set includes any votes directly referenced in the body of the article. We incorporate all of these important votes into our analysis, rather than only examining the CQ “key votes,” because the number of foreign policy “key votes” is relatively small.

We only coded domestic policy votes from every third year because of the amount of time involved in coding a large number of votes. Given that constraint, coding votes from every third year, rather than every other year or every fourth year, prevents the introduction of bias that could be associated with overrepresentation or underrepresentation of presidential or congressional election years, which might feature different patterns of bipartisanship than non-election years. Accordingly, the tabulations presented in this chapter incorporate important domestic policy votes from 1992, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013, and 2016. We started this set of years in 1992, rather than 1991, so that the set as a whole would be temporally balanced between the start and end of the full data set, which runs from 1991 to 2017.

Among a random sample of 25 of the 72 immigration votes in the data set, we found that 12 principally concerned domestic dimensions of immigration policy, 10 principally concerned cross-border dimensions of immigration policy, and 3 concerned both to a large degree.

Unless otherwise noted, differences in all comparisons presented in this chapter are statistically significant at the 1 percent level. We determined the statistical significance of differences for dichotomous measures using chi-squared tests. We determined the statistical significance of differences for continuous measures using t-tests.

More specifically, strength of bipartisanship represents 1—(the absolute value of (the proportion of Republicans voting in favor of the legislation—the proportion of Democrats voting in favor of the legislation)).

CQ Almanac lists votes on which the president took a clear public position in tables entitled “Presidential Position Votes,” which are located within an “Appendix” section entitled “Presidential Support.”

We separately compared patterns of bipartisanship when the chamber of Congress where the vote occurred was controlled by the President’s party with patterns when it was controlled by the opposition party. Interestingly, as can be seen in Appendix Table 10, the percentage of foreign policy votes that are bipartisan is almost identical when the chamber is controlled by the President’s party and when it is not. Appendix Table 11, however, shows that anti-presidential bipartisanship is far more likely when the chamber is controlled by the opposition party. In other words, party control does not alter the likelihood of foreign policy bipartisanship within the chamber, but it does impact the chamber’s relationship with the President.

References

- Alduncin, A., D.C.W. Parker, and S.M. Theriault. 2017. Leaving on a Jet Plane: Polarization, Foreign Travel, and Comity in Congress. Congress and the Presidency 44: 179–200. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Baldassarri, D., and A. Gelman. 2008. Partisans without Constraint: Political Polarization and Trends in American Public Opinion. American Journal of Sociology 114: 408–446. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Baldwin, R.E., and C.S. Magee. 2000. Is Trade Policy for Sale? Congressional Voting on Recent Trade Bills. Policy Choice 105: 79–101. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bendix, W., and G.-H. Jeong. 2020. Beyond Party: Ideological Convictions and Foreign Policy Conflicts in the US Congress. Paper Presented at Workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy. Heidelberg University.

- Baumgartner, F.R., J.M. Berry, M. Hojnacki, B.L. Leech, and D.C. Kimball. 2009. Lobbying and Policy Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Berry, J.M., and C. Wilcox. 2009. The Interest Group Society. New York: Pearson. Google Scholar

- Böller, F., and M. Müller. 2018. Unleashing the Watchdogs: Explaining Congressional Assertiveness in the Politics of US Military Interventions. European Political Science Review 10: 637–662. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bonica, A. 2013. Ideology and Interests in the Political Marketplace. American Journal of Political Science 57: 294–311. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Busby, J., C. Kafura, D. Smeltz, J. Tama, J. Monten, J.D. Kertzer, and B. Helm. 2020. Coming Together or Coming Apart? Attitudes of Foreign Policy Opinion Leaders and the Public in the Trump Era. Chicago: Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Google Scholar

- Canes-Wrone, B., W. G. Howell, and D. E. Lewis. 2008. Toward a Broader Understanding of Presidential Power: A Reevaluation of the Two Presidencies Thesis. Journal of Politics 70: 1–16.

- Carter, R.G., and J.M. Scott. 2009. Choosing to Lead: Understanding Congressional Foreign Policy Entrepreneurs. Durham: Duke University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Chaudoin, S., H.V. Milner, and D.H. Tingley. 2010. The Center Still Holds: Liberal Internationalism Survives. International Security 35: 75–94. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cronin, P., and B.O. Fordham. 1999. Timeless Principles or Today’s Fashion? Testing the Stability of the Linkage between Ideology and Foreign Policy in the Senate. Journal of Politics 61: 967–998. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Curry, J.M., and F.E. Lee. 2020. The Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Delaet, C.J., and J.M. Scott. 2006. Treaty-Making and Partisan Politics: Arms Control and the U.S. Senate, 1960–2001. Foreign Policy Analysis 2: 177–200. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Drezner, D.W. 2019. This Time is Different: Why U.S. Foreign Policy will Never Recover. Foreign Affairs 98: 10–17. Google Scholar

- Drutman, L. 2020. Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America. New York: Oxford University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Edelson, C. 2016. Power Without Constraint: The Post-9/11 Presidency and National Security. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Google Scholar

- Fleisher, R., J.R. Bond, G.S. Krutz, and S. Hanna. 2000. The Demise of the Two Presidencies. American Politics Quarterly 28: 3–25.

- Flores-Macías, G.A., and S.E. Kreps. 2013. Political Parties at War: A Study of American War Finance, 1789–2010. American Political Science Review 107: 833–848. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Flynn, M., and B.O. Fordham. 2021. Everything Old is New Again: The Persistence of Republican Opposition to Multilateralism in American Foreign Policy. Working Paper.

- Flynn, M.E. 2014. The International and Domestic Sources of Bipartisanship in U.S. Foreign Policy. Political Research Quarterly 67: 398–412. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fordham, B.O., and T.J. Mckeown. 2003. Selection and Influence: Interest Groups and Congressional Voting on Trade Policy. International Organization 57: 519–549. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fowler, L.L. 2015. Watchdogs on the Hill: The Decline of Congressional Oversight of U.S. Foreign Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Friedrichs, G. 2020. Polarized We Trade? Intra-Party Polarization and U.S. Trade Policy. Paper Presented at Workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy. Heidelberg University.

- Friedrichs, G. 2021. U.S. Global Leadership and Domestic Polarization: A Role Theory Approach. New York: Routledge. Google Scholar

- Goldgeier, J., and E.N. Saunders. 2018. The Unconstrained Presidency: Checks and Balances Eroded Long Before Trump. Foreign Affairs 97: 144–156. Google Scholar

- Gries, P.H. 2014. The Politics of American Foreign Policy: How Ideology Divides Liberals and Conservatives Over Foreign Affairs. Stanford: Stanford University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Haesebrouck, T., and P. Mello. 2020. Patterns of Political Ideology and Security Policy. Foreign Policy Analysis 16: 565–586. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hafner-Burton, E.M., T. Kousser, and D.G. Victor. 2015. Lobbying at the Water's Edge: Corporations and Congressional Foreign Policy Lobbying. ILAR Working Paper.

- Harbridge, L. 2015. Is Bipartisanship Dead? Policy Agreement and Agenda-Setting in the House of Representatives. New York: Cambridge University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Hicks, K.H., L. Lauter, and C. Mcelhinny. 2018. Beyond the Water’s Edge: Measuring the Internationalism of Congress. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield. Google Scholar

- Hildebrandt, T., C. Hillebrecht, P.M. Holm, and J. Pevehouse. 2013. The Domestic Politics of Humanitarian Intervention: Public Opinion, Partisanship, and Ideology. Foreign Policy Analysis 9: 243–266. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hiscox, M.J. 2002. International Trade and Political Conflict: Commerce, Coalitions, and Mobility. Princeton: Princeton University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Homan, P., and J.S. Lantis. 2020a. The Battle for U.S. Foreign Policy: Congress, Parties, and Factions in the 21st Century. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. BookGoogle Scholar

- Homan, P., and J.S. Lantis. 2020b. Foreign Policy Free Agents: How Lawmakers and Coalitions on the Political Margins Help Set Boundaries for U.S. Foreign Policy. Paper Presented at Workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy. Heidelberg University.

- Howell, W.G., S.P. Jackman, and J.C. Rogowski. 2013. The Wartime President. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Howell, W.G., and J.C. Pevehouse. 2007. While Dangers Gather: Congressional Checks on Presidential War Powers. Princeton: Princeton University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Hurst, S., and A. Wroe. 2016. Partisan Polarization and US Foreign Policy: Is the Centre Dead or Holding? International Politics 53: 666–682. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Iyengar, S., Y. Lelkes, M. Levendusky, N. Malhotra, and S.J. Westwood. 2019. The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science 22: 129–146. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jacobson, G.C. 2013. Partisan Polarization in American Politics: A Background Paper. Presidential Studies Quarterly 43: 688–708. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jeong, G.-H., and P.J. Quirk. 2019. Division at the Water’s Edge: The Polarization of Foreign Policy. American Politics Research 47: 58–87. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jochim, A.E., and B.D. Jones. 2013. Issue Politics in a Polarized Congress. Political Research Quarterly 66: 352–369. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kelley, J.G., and J.C.W. Pevehouse. 2015. An Opportunity Cost Theory of US Treaty Behavior. International Studies Quarterly 59: 531–543. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kertzer, J.D., S.G. Brooks, and D.J. Brooks. Forthcoming. Do Partisan Types Stop at the Water's Edge? Journal of Politics.

- Klein, E. 2020. Why We’re Polarized. New York: Simon & Schuster. Google Scholar

- Krasner, S.D. 1978. Defending the National Interest: Raw Materials Investments and U.S. Foreign Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Google Scholar

- Kriner, D.L. 2010. After the Rubicon: Congress, Presidents, and the Politics of Waging War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Kriner, D.L. 2014. Obama’s Authorization Paradox: Syria and Congress’s Continued Relevance in Military Affairs. Presidential Studies Quarterly 44: 309–327. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kupchan, C.A., and P.L. Trubowitz. 2007. Dead Center: The Demise of Liberal Internationalism in the United States. International Security 32: 7–44. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lantis, J.S. 2019. Foreign Policy Advocacy and Entrepreneurship: How a New Generation in Congress is Shaping US Engagement with the World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Lapinski, J. 2013. The Substance of Representation: Congress, American Political Development, and Lawmaking. Princeton: Princeton University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Lee, C.A. 2019. Electoral Politics, Party Polarization, and Arms Control: New START in Historical Perspective. Orbis 63: 545–564. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lee, F.E. 2009. Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Lee, F.E. 2016. Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Leech, B.L. 2011. Lobbying and Interest Group Advocacy. In The Oxford Handbook of the American Congress, ed. E. Schickler and F.E. Lee. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Google Scholar

- Lewis, V. 2019. Ideas of Power: The Politics of American Party Ideology Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Marshall, B.W., and P.J. Haney. 2010. Aiding and Abetting: Congressional Complicity in the Rise of the Unitary Executive. In The Unitary Executive and the Modern Presidency, ed. R.J. Barilleaux and C.S. Kelley. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. Google Scholar

- Marshall, B.W., and P.J. Haney. 2020. The Impact of Party Conflict on Executive Ascendancy and Congressional Abdication in US Foreign Policy. Paper Presented at Workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy. Heidelberg University.

- Marshall, B.W., and B.C. Prins. 2007. Strategic Position Taking and Presidential Influence in Congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly 32: 257–284. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Martin, L.L. 2000. Democratic Commitments: Legislatures and International Cooperation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Mason, L. 2018. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Maxey, S. 2018. Finding the Water's Edge: When Partisanship Influences Foreign Policy Attitudes. Paper Presented at the International Studies Association Annual Conference.

- Maxey, S. 2020. The Power of Humanitarian Narratives: A Domestic Coalition Theory of Justifications for Military Action. Political Research Quarterly 73: 680–695. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mayhew, D.R. 2005. Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946–2002. New Haven: Yale University Press. Google Scholar

- Mccarty, N., K.T. Poole, and H. Rosenthal. 2016. Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches. Cambridge: MIT Press. Google Scholar

- McCormick, J.M., and E.R. Wittkopf. 1990. Bipartisanship, Partisanship, and Ideology in Congressional-Executive Foreign Policy Relations, 1947–1988. Journal of Politics 52: 1077–1100. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- McCormick, J.M., and E.R. Wittkopf. 1992. At the Water’s Edge: The Effects of Party, Ideology, and Issues on Congressional Foreign Policy Voting, 1947–1988. American Politics Quarterly 20: 26–53. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Meernik, J. 1993. Presidential Support in Congress: Conflict and Consensus on Foreign and Defense Policy. Journal of Politics 55: 569–587. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Meernik, J., and E. Oldmixon. 2008. The President, the Senate, and the Costs of Internationalism. Foreign Policy Analysis 4: 187–206. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Milner, H.V., and D. Tingley. 2015. Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Google Scholar

- Myrick, R. 2019. Do External Threats Unite or Divide? Security Crises, Rivalries, and Polarization in American Foreign Policy. Paper Presented at American Political Science Association Annual Meeting.

- Myrick, R. 2020. The Reputational Consequences of Polarization for American Foreign Policy: Evidence from the U.S.-U.K. Bilateral Relationship. Paper Presented at Workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy. Heidelberg University.

- Noel, H. 2013. Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America. New York: Cambridge University Press. Google Scholar

- Peake, J.S., G.S. Krutz, and T. Hughes. 2012. President Obama, the Senate and the Polarized Politics of Treaty-Making. Social Science Quarterly 93: 1295–1315. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Prather, L. 2016. Values at the Water's Edge: Social Welfare Values and Foreign Aid. Working Paper.

- Prins, B.C., and B.W. Marshall. 2001. Congressional Support of the President: A Comparison of Foreign, Defense, and Domestic Policy Decision Making during and after the Cold War. Presidential Studies Quarterly 31: 660–678. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rathbun, B. 2016. Wedges and Widgets: Liberalism, Libertarianism, and the Trade Attitudes of the American Mass Public and Elites. Foreign Policy Analysis 12: 85–108. Google Scholar

- Rathbun, B.C. 2012. Trust in International Cooperation: International Security Institutions, Domestic Politics and American Multilateralism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Google Scholar

- Raunio, T., and W. Wagner. 2020. The Party Politics of Foreign and Security Policy. Foreign Policy Analysis 16: 515–531. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rozell, M.J., C. Wilcox, and M.M. Franz. 2012. Interest Groups in American Campaigns: The New Face of Electioneering. New York: Oxford University Press. Google Scholar

- Rudalevige, A. 2006. The New Imperial Presidency: Renewing Presidential Power after Watergate. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Google Scholar

- Schultz, K.A. 2001. Democracy and Coercive Diplomacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Schultz, K.A. 2017. Perils of Polarization for U.S. Foreign Policy. Washington Quarterly 40: 7–28. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Scott, J.M., and R.G. Carter. 2014. The Not-So-Silent Partner: Patterns of Legislative-Executive Interaction in the War on Terror, 2001–2009. International Studies Perspectives 15: 186–208. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sigelman, L. 1979. A Reassessment of the Two Presidencies Thesis. Journal of Politics 41: 1195–1205.

- Smeltz, D., J. Busby, G. Holyk, C. Kafura, J. Monten, and J. Tama. 2015. United in Goals, Divided on Means: Opinion Leaders Survey Results and Partisan Breakdowns from the 2014 Chicago Survey of American Opinion on US Foreign Policy. Chicago: Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Google Scholar

- Smeltz, D., I. Daalder, K. Friedhoff, C. Kafura, and B. Helm. 2020. Divided We Stand: Democrats and Republicans Diverge on US Foreign Policy. Chicago: Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Google Scholar

- Snyder, J., R.Y. Shapiro, and Y. Bloch-Elkon. 2009. Free Hand Abroad, Divide and Rule at Home. World Politics 61: 155–187. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tama, J. 2018. The Multiple Forms of Bipartisanship: Political Alignments in US Foreign Policy. Brooklyn: Social Science Research Council. Google Scholar

- Tama, J. 2020. Forcing the President’s Hand: How the US Congress Shapes Foreign Policy through Sanctions Legislation. Foreign Policy Analysis 16: 397–416. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Theriault, S.M. 2008. Party Polarization in Congress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Theriault, S.M. 2013. The Gingrich Senators: The Roots of Partisan Warfare in Congress. Oxford: Oxford University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Thurber, J.A., and J. Tama, eds. 2018. Rivals for Power: Presidential Congressional Relations, 6th ed. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Trubowitz, P., and P. Harris. 2019. The End of the American Century? Slow Erosion of the Domestic Sources of Usable Power. International Affairs 95: 619–639. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wagner, W. 2020. The Democratic Politics of Military Interventions: Political Parties, Contestation, and Decisions to Use Force Abroad. Oxford: Oxford University Press. BookGoogle Scholar

- Wenzelburger, G., and F. Böller. 2019. Bomb or Build? How Party Ideologies Affect the Balance of Foreign Aid and Defence Spending. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22: 3–23. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wildavsky, A. 1966. The Two Presidencies. Transaction 4: 7–14. Google Scholar

- Zelizer, J.E. 2010. Arsenal of Democracy: The Politics of National Security—From World War II to the War on Terrorism. New York: Basic Books. Google Scholar

Funding

Funding was provided by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and Social Science Research Council.